Outreach Lessons from an Artist: Behavior Change Design

POSTED ON April 24th, 2015 BY Nancy Roberts A stunning art installation featuring the plight of political prisoners around the world got me thinking about, yes, recycling campaigns. In addition to being a moving experience, the @Large exhibit by Chinese artist Ai Wei Wei , on now at Alcatraz Island, nicely illustrates the stages we consider when designing a campaign for environmental behavior change. The exhibit takes the viewer along a path, with different appeals and presentations at each step.

A stunning art installation featuring the plight of political prisoners around the world got me thinking about, yes, recycling campaigns. In addition to being a moving experience, the @Large exhibit by Chinese artist Ai Wei Wei , on now at Alcatraz Island, nicely illustrates the stages we consider when designing a campaign for environmental behavior change. The exhibit takes the viewer along a path, with different appeals and presentations at each step.

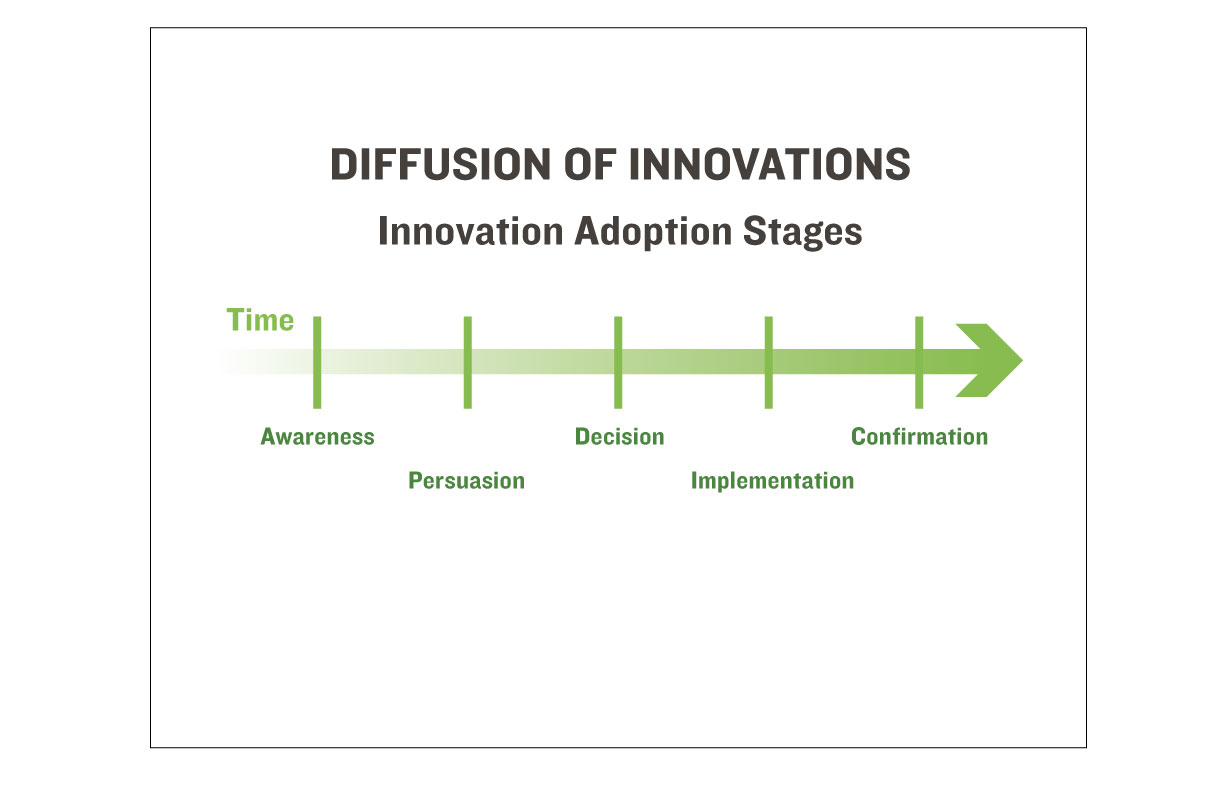

People need to come to behavior change through a process, most clearly described by Everett Rogers back in the 1960s in his book, Diffusion of Innovations. His Innovation Adoption Stages model looks like this:

Intentionally or not, the Ai Wei Wei installation follows the stages, leading the visitor from awareness of the issues, through “persuasion” via a multi-sensory deepening of the experience, and finally, offers a concrete action that the viewer can take.

The @Large installation begins at the New Industries Building. It takes several forms, but the initial contact focuses on making the viewer aware of the variety and extent of political imprisonment around the world. The floor of an enormous room is covered with portraits of political prisoners, made from LEGO bricks. At this point, the artist has not assumed that the viewer is ready to do something, but rather provides beautifully crafted “information” in the form of portraits of human faces arrayed across a huge space to raise awareness of the scope of the issue. Books detailing the stories of each of the prisoners are present, but the viewer is not in any way forced to learn more facts and figures. The act of walking the length of the huge room with the 176 portraits “sets the problem” in the mind and heart of the visitor.

The @Large exhibit continues to the cell block building, where the viewer starts to live into the experience of prisoners – visitors are invited to enter each of 12 small, unadorned and definitely not prettified cells. There is nothing to look at, but each cell has a different recording playing, usually of the music or speech of one of the prisoners. By involving the sense of hearing and the physical experience of walking into the tiny, dingy cells, the viewer becomes more fully involved and engaged.

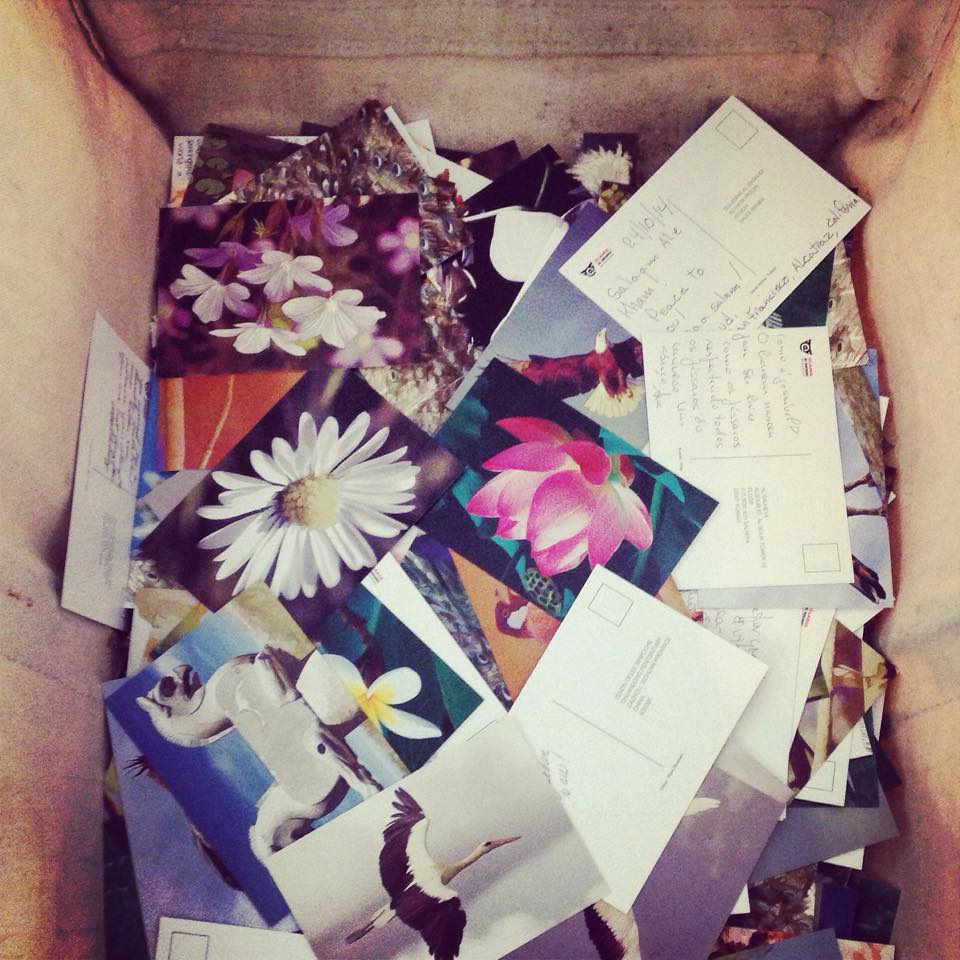

After several more stops, at the end of the exhibition visitors are given the opportunity to write postcards addressed to individual prisoners whose portraits they saw earlier. The sponsoring Foundation notes: “The postcards are adorned with images of birds and plants from the nations where the prisoners are held. Cards are gathered and mailed by @Large Art Guides.”

The viewer has been led through awareness of the issue to persuasion about the problem’s scope and importance, though information and appeals to the emotions. Only at the end is the viewer invited to make a decision to act, by writing a personal communication to one of the prisoners introduced during the first stop of the exhibition. The viewer is not urged to act before s/he has had a chance to fully digest and explore the need to communicate. And by communicating, not to a general, amorphous authority, but to a single individual, the final action becomes that much more memorable.

Not all of our behavior change campaigns can be as beautiful and meaningful as Ai Wei Wei’s @Large, but there is much to admire in the intentional layout of the exhibit that aims to touch, inspire and ultimately, change the viewer. The exhibit ends this month…go see it if you can!

@Large: Ai Weiwei on Alcatraz is presented by the FOR-SITE Foundation in partnership with the National Park Service and the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy.