OK, we admit it: we’re waste word wonks. But when it comes to encouraging correct recycling behavior, words are the key to deeds.

In our work with client agencies, we’ve noticed that some recycling coordinators and others are discouraged: they’ve been doing outreach for years, and yet they feel it hasn’t worked. Some in the industry are turning to new technologies that divert waste without having to address those elusive behavioral issues. We also observe that the average citizen is presented with different terms and other mixed messages about waste. As a first step to addressing this issue, we conducted a survey to test current understanding of waste terms and processes among Californian adults.

We surveyed Californians up and down the state, testing their understanding of terms like “diversion” and “biodegradable.” We also asked people where they would put various discarded items (e.g., an orange rind or used napkin) when presented with bins having different labeling systems.

While most respondents were clear that soda cans go into the Recycling bin, there was significant confusion on where to put items like potato chip bags, used napkins, and especially plastic forks. No wonder there is a lot of contamination in the waste stream when 70% of respondents think plastic forks should go into the Recycling bin. (They are not recyclable in most jurisdictions.) Some 40% of respondents would put a used napkin in a bin marked Garbage, while only 33% would put it in a bin marked Landfill; over one-third would put a used napkin in Recycling.

The most revealing result of the survey came from a question about how consumers understand what happens in a landfill. Here is the breakdown of responses:

What happens at a Landfill? (choose one)

| Answer Options | Response Percent |

| Waste is sorted into recyclables and garbage. Recyclables go somewhere else. Garbage is buried there and breaks down. | 26.9% |

| Waste is sorted into recyclables and garbage. Recyclables go somewhere else. Garbage is buried there, where it stays forever. | 34.5% |

| Anything that is thrown away, including garbage and recyclables, gets dumped and most of it breaks down. | 33.0% |

| Dirt is dumped to make usable land for building homes, offices, etc. | 5.6% |

Some 60% of respondents think that most of what goes to Landfill (whether it be Garbage or even Garbage and Recyclables) eventually breaks down. If a person believes that Landfilled objects break down over time anyway, s/he probably has much less incentive to keep things out of Landfill. I mean, it all goes “away,” right? Wrong. Clearly, there is outreach work to be done.

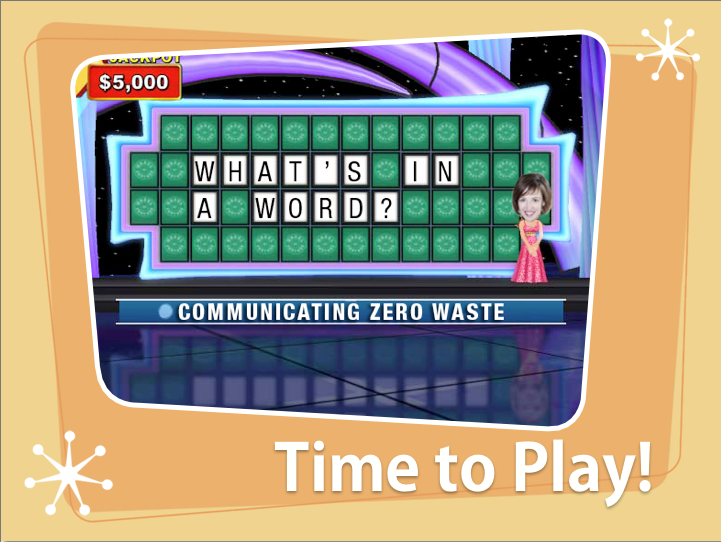

Results of the survey were presented at this month’s California Resource Recovery Association conference. And we do mean presented: we used a game show format, with Gigantic staff taking the roles of MC and answer  wonks, with Gigantic principal Shana McCracken giving a fine imitation of Vanna White. Environmental professionals from northern California were pitted against three pros from the southern end of the state, in a test to see if industry insiders could guess how the majority of “regular citizens” responded to particular survey questions. Congrats to the winning team from SoCal, pictured right, who captured the coveted Golden Garbage Can award, and many thanks to the good sports on the NorCal team, below.

wonks, with Gigantic principal Shana McCracken giving a fine imitation of Vanna White. Environmental professionals from northern California were pitted against three pros from the southern end of the state, in a test to see if industry insiders could guess how the majority of “regular citizens” responded to particular survey questions. Congrats to the winning team from SoCal, pictured right, who captured the coveted Golden Garbage Can award, and many thanks to the good sports on the NorCal team, below.

If you would like a free copy of the full Waste Terms Survey results, please email us.

The survey is just one step toward achieving Zero Waste in California. Here at Gigantic Idea Studio, we believe more effective research focused on communications and carefully crafted outreach are both part of the answer. We’re not prepared to give up on the human race just yet.